Swerved for too long, it's time our leaders began to solve Britain's shabby prisons

Our prisons are bursting at the seams, crime often goes unnoticed, more and more victims are feeling powerless. How long is it before we say enough is enough?

If you were to take a leisurely weekend stroll along Oxford Street in central London with your mobile phone exposed, there is a high likelihood it would be stolen. A while ago, that used to be a situation only familiar to a minority; now it’s a regular occurrence. You could say that any individual silly enough to have their phone revealed to fellow members of the public on one of the country’s — and Europe’s — busiest streets would get what they deserved. Or you might ask why they had it clutched in their hand, in open view to all the potential moped-riding crooks roaming around the capital. And on both points, you would have made entirely reasonable judgments.

In a city as large as London, where millions of people converge on bridges, buses, rail networks, and streets each day, such crimes are, it is often said, unavoidable. To which I would say, there is a modicum of justification: in a metropolis of nearly nine million people, crimes such as theft and anti-social behaviour are not so much inevitable but probable to occur at some point. But it feels, as it does nationwide, that we have reached a tipping point.

I write this in the wake of a video published on Thursday by Robert Jenrick, Tory justice spokesman and ex-leadership contender, in which he challenges those refusing to pay their fares at Stratford station, east London, by pushing through barriers without any consequence. (At the time of writing, the video has been viewed more than fourteen million times on X.)

Cards on the table here: I hold little time for Mr Jenrick, nor for his noted omissions to his party’s pretty shoddy record on crime and law and order when in government, during which frontline policing in the 2010s plummeted, the prison system exploded, the effects of which are now rearing its head, and the backlogs in our courts reached a pinnacle. Worst of all, Mr Jenrick has served under the past five Tory leaders in some capacity or another, four of whom were when the party were in government; so whilst he may view the Tories’ period in office as one which Labour might seek to replicate, on crime and law and order another story is played out.

But still. Despite my reservations about Mr Jenrick, he has, whether justified in doing so or not, reminded us of the vast increase in lawlessness, coupled with the decline of social order, which so many people feel across the country. For which, yes, in large part, his party is to blame. But aside, much more importantly, this is no longer a thing, or a feeling with which only a minority can associate; it’s becoming, especially if you’re living in a highly populated city, a more frequent reality.

As this lawlessness has taken shape, so many parts of society have become so apathetic that their confidence in, and trust of, the police to solve crime and do justice to perpetrators and victims has plunged. People who now find themselves unlucky to have their phone pinched on Oxford Street, their bag stolen on the way to work, their privacy invaded on the transport network by a crook up to no good, and so many other victims of crime to whom they will relate, lack the necessary energy to pursue seemingly endless forms of complaint, procedure and follow-up investigations with the police.

This is not to say victims of crime shouldn’t report what has happened to them — far from it — but to note the low-trust society into which Britain has morphed and how so many victims of crime, increasing in number, don’t bother reporting incidents because they don’t believe justice will be delivered. It is not difficult to see why: on cases related to sexual offences alone, Rape Crisis England and Wales informs us that there stand near to twelve thousand cases waiting to go to crown court, an increase of more than forty per cent compared with just two years ago. And so is it any wonder why victims lack the necessary zeal to pursue their case and to recall what has occurred to them, often a harrowing and tormenting experience in and of itself, especially when backlogs in our courts — a record high of more than 73,000 in September last year — are at breaking point.

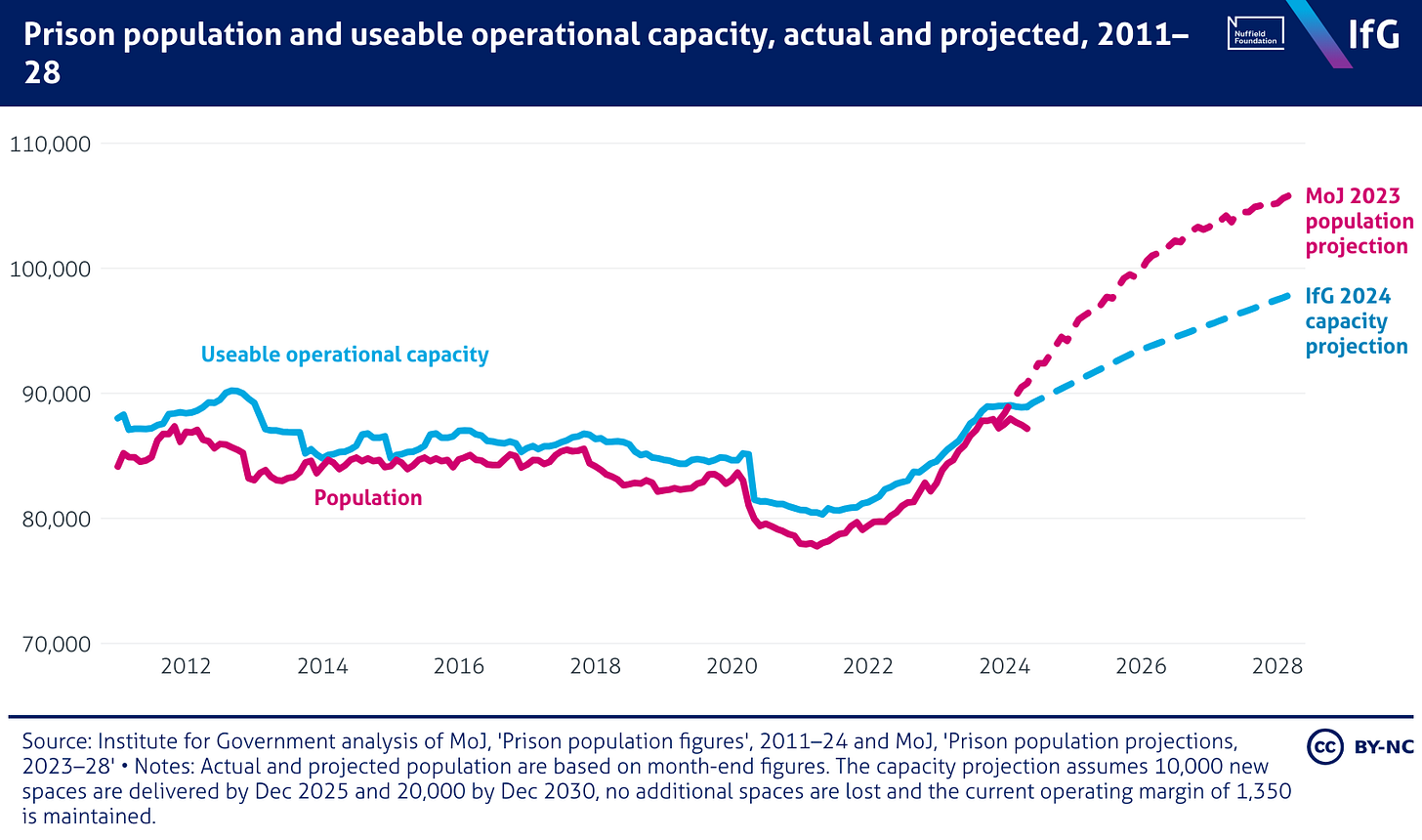

Which brings me to the breaking point situation in our prisons. The Institute for Government notes that the prison population has continued to increase, while crime rates have steadily fallen since around the mid-1990s. In May 2020, as Covid began to sweep the country, the prison population stood just shy of 80,000; four years later, in May 2024, this had soared to more than 87,000. And yet this crisis has festered and lingered for years, partly because the politicians whom we elect, or rather those ministers at the Ministry of Justice, have lacked the enthusiasm to build more prisons, not simply for today and the here and now but for tomorrow and future decades, too. This is no longer a question of whether politicians should be tackling this issue of prison overcrowding; it’s arguably a national emergency as prisoners throng into crowded cells, the health (mental and physical) risks to them and their fellow inmates growing further with each week that passes.

So important is it for our leaders to tackle this emergency that the numbers continue to stack up, with reoffending rates in England and Wales costing the government nearly £24 billion a year. And as this crisis continues to escalate, it is critical to emphasise the importance of rehabilitation. This is not simply good for the country or indeed the justice system, but for the individual at heart. The chance for them to re-integrate into society, have a stake in their local community, enter into employment, and provide for their family can often be life-defining moments for many individuals whose status in prison is neither deserved nor beneficial. There are many in prison for whom rehabilitation is quite justifiably not an option, but such a message is crucial for those with the least serious offences.

Leaders have ducked the tricky issue of prison reform for too long, for fear of accusations of being soft on crime and law and order. But as this crisis continues to manifest further, no longer is it the time to duck, sidestep and weave: our justice system and our prisons need bold action and solid reform, and soon.